It’s Been Real

Ever since I decided that I wanted to be a teacher, I’ve approached every class with pretty much the same mentality: what can I learn from this class about how to teach? Even if the subject matter of the class itself is totally unrelated to English or teaching, I still try to collect all of the information I can about how a successful classroom works and what I can do in the future to keep all of the good ideas and ditch all the things that don’t work. The more I learn about teaching, the more my former beliefs about what it means to be a teacher break down. I’m beginning to realize that this job is going to be a lot more difficult than I first imagined — but also way, WAY more creative, reflective, and awesome than I first imagined!

The interesting thing about this class is that I definitely feel like it has shaped and changed who I will be as a teacher, but it has done so largely by breaking down and destroying ideas that I used to have, and I don’t necessarily feel like I have clear and cohesive replacement ideas for what to do instead. For instance, I absolutely love the idea that Kim has modeled in her class of not just “playing school” with quizzes and points and such. As much as possible, I want to shoot for more of a credit-or-no-credit style grading when I am a teacher; if you do the thing, you get the points. If you don’t do the thing, no points. If you half-ass the thing, you do it again, and then you get the points. While this won’t work with everything in high school, I think a lot of things could be graded this way, particularly writing assignments, and I think there could be an enormous benefit to trying this.

One of my favorite concepts from this class has been the intersection of literacy and identity, and this is something which I’m not yet quite sure how to incorporate into a classroom. I think this is where choice in assignment can come in; assignments like the inquiry paper and the 20Time/Genius Hour project can allow students to pursue their own interests and express their emerging identities, or help them to discover new ones. In an article I read for another class, a junior high boy is quoted saying “School only teaches you how you are dumb, not how you are smart.” This boy was expressing frustration with the fact there are always new things to be learned in school, and little to no space for expressing and enjoying what you already know and are good at. Inquiry and choice-based projects can reverse this by giving students a space where they can be the experts, pursuing something they are excited about or expanding their knowledge in a field they already enjoy.

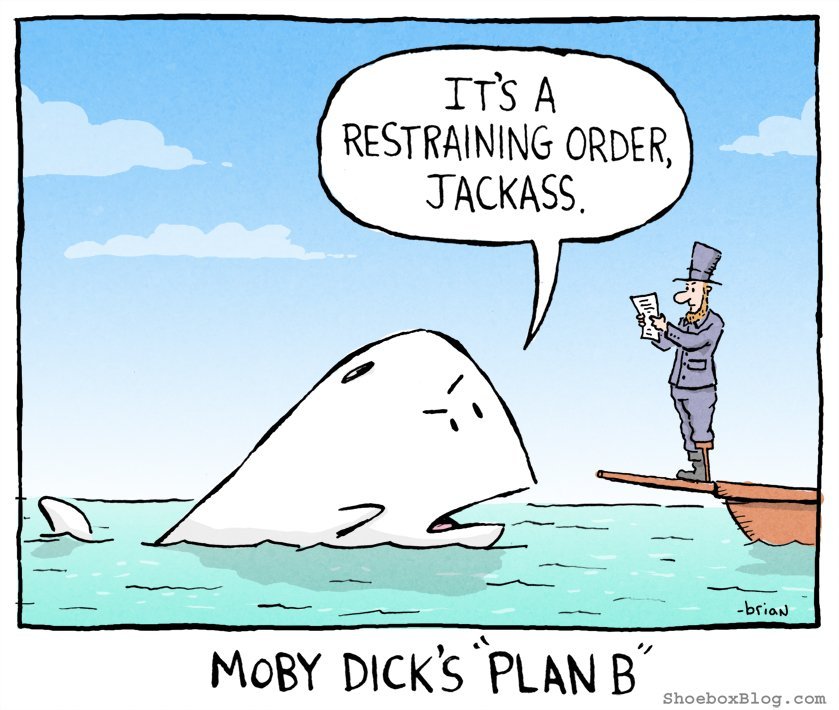

Additionally, though, I think there is something to be said on behalf of exposure. I probably wouldn’t identify as a backpacker and outdoorsy person today if my friends Ben and Sean hadn’t half-forced me to go on a trip to Yosemite with them back in 2008. Similarly, many students might not know they are readers and writers, or certain kinds of readers and writers, until we compel them to try out different things. This is why I think there is still a place in the curriculum for classic literature alongside the free choice projects; the key, of course, is to make the classic literature not suck. This is where my other favorite part of this class comes in: The book about re-mixing and remediating Moby Dick! While there are a few books still taught in school which truly are the worst, I generally really like literature, and I passionately believe that there are ways to help students connect with literature – we just have to break away from the ol’ “read out loud, read at home, take a quiz in class, write an essay, repeat” method, and get creative. I think that having a production-centered classroom is key to this; students should always be making things informed and inspired by the texts they are reading in class – and I don’t mean more essays. Have them write raps and skits, or translate the text into their own words; have them write fanfiction which answers a question that a reader might have after finishing the book, make a video or trailer for the book, or draw a few pages of their own graphic novel interpretation of the book. Host a debate in class over an issue (imaginary or real-world) inspired by the book. Research the historical context of the book, and do stuff with that. The list goes on and on to the point that I really feel like there is no excuse for doing the same ol boring thing in class every day.

More than anything else, though, this class has simply changed my perspective on literacy and learning. I never considered myself to be a person with a deficit view of students, but I realize now that I kind of was – at least in certain ways. I’ve definitely always bought into the “literacy crisis” rhetoric, mostly because I’d never heard an argument to the contrary. I’ve also always gotten a weird OCD joy out of “correcting” other people’s papers, which I now realize is kind of effed up, as I have gained a whole new understanding and appreciation for how to encourage and develop literacies in students. (The word “correcting” kind of makes me shudder now, actually.) I’ve also never thought about things like texting, tweeting, or gaming as genuine, legitimate skills and types of literacy. In general, I feel like I have gained a whole new lense with which to look at people and notice all of the ways in which they are incredibly literate and talented and awesome in ways that I never noticed before. I’ve never bought into the “blank slate” idea, thankfully, but now I really totally super don’t buy into it ;) Now, whenever I hear someone ranting about kids these days always playing video games and texting and wasting their lives and not being able to read a book or whatever, I have to genuinely restrain myself from jumping into the conversation with a “Well actually…” I feel that I am more prepared to be a teacher because of this class; not so much because I’ve learned a whole bunch of new information, but because my perspective has shifted, widened, and deepened.

Website:

Website: