Participatory Classrooms

Reading in a Participatory Culture (RIAPC, for the purposes of this blog) draws upon modern understandings of participation and remix to make the argument that Language Arts classrooms should be spaces in which students are encouraged to participate in literature, not just consume it. The book follows the inception, progress, and performance of Ricardo Pitts-Wiley’s play “Moby Dick: Then and Now”, which he wrote with the heavy involvement of students at an urban high school who were reading Moby Dick for the first time. Pitts-Wiley describes the profound way in which his students connected with the book, spurred on by the process of making connections between the themes and characters and real-life, modern scenarios that they were familiar with.

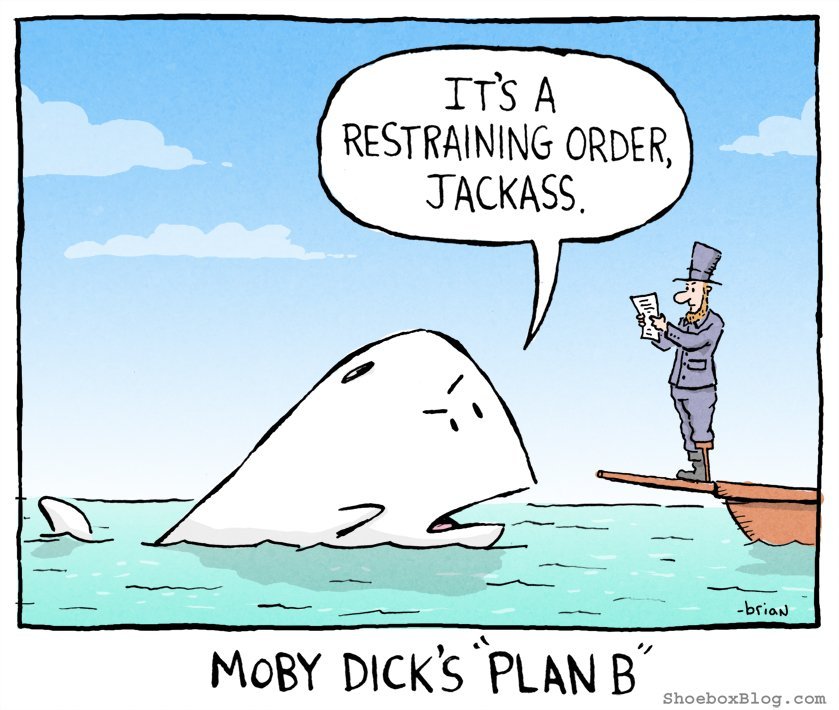

One of my favorite parts of the book was a section which discussed the differences and intersections between remix and appropriation (including stuff such as fan fiction) and notions of plagarism and “stealing”. Interestingly, the authors of RIAPC hold a view of fanfic – or at least of some fanfic – which was, to me, surprisingly positive. RIAPC draws a meaningful distinction between plagarism and appropriation, and between thoughtful remixes and lazy ones, which I found to be incredibly insightful and useful to anyone considering the use of remixes in their classroom. According to the book, the difference between plagarism and appropriation/remix has to do with credit for ideas. In plagarism, one author takes on the content or ideas of another and attempts to pass them off as his or her own; the original source is purposefully concealed. A remix, however, is open about its original source material; in fact, a really good remix likely depends on it’s reader/viewer’s knowledge of the original source in order to be understood. In this vein, RIAPC indicates that some remixes are better than others. A truly thoughtful remix actually requires a deep understanding of the original work, and will expand on, question, or poke fun at elements of the work in a way which can only come from someone who has read and understood the original. By these standards, some fan fictions can actually be great examples of a thoughtful remix, such as ones which write to fill in a plot hole, who carry on after the story has ended, or who write from a minor character’s perspective. A shallow remix, on the other hand, is one which demonstrates little knowledge of or respect for the original work. I found this section of clarifications really useful, and I think that it would be the start of a great class discussion to hold before my future class begins working on our own remixes!

My only argument with the book is that I would have loved to receive even more real-life advice about diverse, manageable ways to implement these remediation ideas in the classroom. The book focuses primarily (almost-but-not-quite exclusively, in fact) on Pitts-Wiley’s play as an example of a masterful student-designed remix of Melville’s classic. While this example is truly awesome, it is also of an incredibly large scale which probably couldn’t be incorporated as-is into the average English classroom. However, the example of the play does serve as an inspirational reminder of what can happen when students are encouraged and given the freedom to dive into a text and make meaning out of it in a way which is relevant to them.

Website:

Website: